Overview

Gross Anatomy

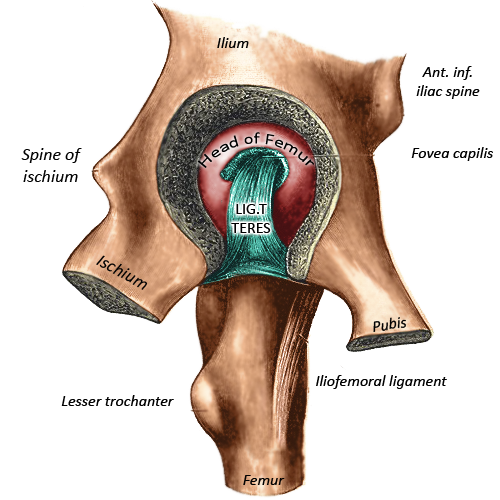

Articular structure

Actions

Blood supply

Nerve Supply

“the nerve supplying

a joint supplies also the muscles which move the joint and the skin covering

the articular insertion of those muscles”(7).

Development

Clinical Anatomy

Femoral neck fractures

Hip

fractures represent a significant public health burden with around

70,000-75,000 cases a year with an estimated cost of £2 billion per a year, 10% of cases die

within one month and a third die within 12 months(10). This is a marker of the

complex co-morbidities of these patients, thus a thorough history into the

cause of the fall needs to be undertaken and all patients should be managed

within a multi-disciplinary environment with orthogeriatric input.

Management

is nearly exclusively surgical with NICE recommending surgery on the day or day

after admission with rapid correction or control of manageable co-morbidities

to facility surgery(10).

Surgical

options depend on the type of fracture. Firstly one must deduce if the fracture

is intra or extra-capsular. In extra-capsular fractures blood supply to the

femoral head is preserved and not threatened. If the fracture is above or

including the lesser trochanter extramedullary fixation such as a sliding hip

screw should be used, if subtrochanteric intramedullary fixation is advisable(10).

Intracapsular

fractures are more complex. Due to the blood supply, as described above, the

viability of the femoral head is threatened and avascular necrosis may occur.

Fixation technique decision is dependent on the degree of displacement.

Displacement is judged on plain film radiographs with both AP and lateral views

assessed. Gardens classification is used to classify femoral neck fractures.

Non displaced fractures (Gardners I and II) undergo fixation with cancellous

scews or sliding hip screw. Displaced fractures (Gardners III and IV) require

arthroplasty due to disruption of the blood and high risk of avascular necrosis

, this can be total hip replacement or hemiarthroplasty(10). Indications for total hip

replacement are defined by NICE as the following:

· Were able to walk

independently out of doors with no more than the use of a stick and

· Are not cognitively

impaired and

· Are medically fit for

anaesthesia and the procedure

Post

operatively early mobilization is the aim with multi-disciplinary

rehabilitation and future falls prevention.

Osteoarthritis

Pain

secondary to osteoarthritis of the hip joint is present in 12% of adults of 65

years and above(11). Osteoarthritis of the hip may

be primary or secondary to previous infection, injury or disease.

Osteoarthritis of the hip joint has a worse prognosis than that of the hand or

knee with a significant proportion requiring operative management at five years(11).

Pain

is often the primary complaint, this can be felt in the anterior groin or it

can be more generalized over the buttock and down to the knee. Patients may

well complain that they find it hard to put on their shoes or cut their toe

nails. Key signs on examination are an antalgic gait, muscle wasting,

painful/reduced range of motion (internal rotation is the first effected), in

later stages a fixed flexion deformity can be found(11).

Diagnosis

can be made clinically, however AP plain film radiographs of the pelvis may

well be useful.

Treatment

should be individualized to patient factors. Education, strengthening with

physiotherapy input, weight loss (if required), activity modification and

assistive devices should be provided. Alongside this appropriate analgesia is

needed. This should initially be paracetamol +/- non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). If prescribing a NSAID a proton-pump

inhibitor should be co-prescribed and NSAIDs are not suitable/appropriate for

all patients. Some may add weak opioids such as codeine however the evidence

for this is poor(11). Intra-articular injection can

also be considered; this may also provide diagnostic information.

If

a patient continues to suffer from significant symptoms and pain operative

intervention may be considered. Surgical options consist of arthroscopy,

osteotomy, hip resurfacing and replacement(12). Patients age and degree of

arthritic changes are key factors in the decision making process.

Developmental dysplasia of the

hip (DDH)

DDH

is a spectrum of disease ranging from mild dysplasia of the acetabulum to

irreducible dislocation. 1-1.5 in 1000 live births are affected and it is more

common in female patients, breech presentation and intra-uterine overcrowding(13,

14). The left hip is

more commonly affected(13,

14).

In

the neonate DDH is asymptomatic and therefore is screened for with Barlow and

Ortolani tests. After the age of around 3 months the tissues begin to tighten

and the aforementioned tests become unreliable, signs at this stage will be

loss of abduction, apparent shortening of the thigh (Galeazzi sign) and

asymmetrical skinfolds (however may be present in normal individuals)(13). After the child begins to walk

other signs such as a trandelenburg gait and leg-length discrepancy will become

apparent.

Ultrasonography

prior to femoral head ossification (4-6 months) and plain film radiographs

after ossification are the mainstay of investigation(13,

14).

Treatment

depends on the age of diagnosis. Ultimately the aim is to maintain a reduced hip

joint providing the optimal environment for normal hip development. As age at

diagnosis increases this is harder to achieve, potential for hip remodeling

reduces and more complex treatments are required. The following gives an overview

of treatment options available according to age(13-15):

Under 6 months

· Splintage usually

with a Pavlik harness

· Monitor with USS

6 months to 18 months

· Closed reduction (+/-

adductor tenotomy)

o If difficulty in

reduction consider arthrogram to assess if soft tissue is blocking reduction

· If closed reduction

fails open reduction

· Reduction (closed or

open) is held with a hip spica cast

18 months to 3 years

· Open reduction (+/-

osteotomy)

3 to 8 years

· Open reduction and

osteotomy

Over 8 years

· Can be treated

non-surgically or with osteotomy

· Irrespective of above

management choice must plan for a total hip replacement in adult life

Quick Anatomy

Key Facts

Development: Derived from the

mesoderm.

Blood

supply: Retinacular vessels (branches of the

circumflex vessels) are the predominant blood supply for the femoral head.

Branches of the internal iliac artery supply the acetabulum.

Nerve

supply: Innervation of the hip joint is from the

femoral, obturator, sciatic nerve, superior gluteal and nerve to the quadratus

femoris.

Aide-Memoire

Summary

The hip joint is a major load bearing ball

and socket joint connecting the pelvis to the lower limb. The joint is very

stable but retains multi-axial movement. Pathological processes can occur in

all stages of life and may well require surgical intervention.

References

1 Weber E, Ritting A. Normal Hip Embryology and

Development. In: Berry D, Lieberman J, editors. Surgery of the Hip. 1 ed:

Elsvier Health Sciences; 2012. p. 200-5.

2 Wheeless C. Embryology of the Hip. In:

Wheeless C, editor. Wheeless' Textbook of Orthopaedics: Duke Orthopaedics;

2013.

3 Moore KL, Dalley AF, II, Agur AMR.

Clinically oriented anatomy. 5th ed. ed. Philadelphia, Pa. ; London: Lippincott

Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

4 Moses K, Banks J, Nava P, Petersen D. Hip

Joint. In: Moses K, Banks J, Nava P, Petersen D, editors. Atlas of clinical

gross anatomy. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2013. p. 512-25.

5 Hoffmann R, Haas N. Fractures of the

femoral neck (31-B). [cited 2016

10/3/16]; Available from: https://www2.aofoundation.org/wps/portal/!ut/p/a0/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfGjzOKN_A0M3D2DDbz9_UMMDRyDXQ3dw9wMDAx8jfULsh0VAdAsNSU!/?bone=Femur&segment=Proximal&soloState=lyteframe&contentUrl=srg/popup/further_reading/PFxM2/31/661_31_fem_neck_fxs_gen_consid.jsp

6 Itokazu M, Takahashi K, Matsunaga T, et

al. A study of the arterial supply of the human acetabulum using a corrosion

casting method. Clin Anat. 1997;10(2):77-81.

7 Hilton law. Farlex Partner Medical Dictionary; 2012.

8 Birnbaum K, Prescher A, Hessler S, Heller

KD. The sensory innervation of the hip joint--an anatomical study. Surg Radiol

Anat. 1997;19(6):371-5.

9 Cheatham SW, Kolber MJ. Orthopedic

management of the hip and pelvis. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier, Inc.; 2016.

10 NICE. Hip fracture: management. National

Institute for Health and Excellence Guidance. 2011 22/06/11.

11 NICE. Osteoarthritis. Clinical Knowledge

Summaries. 2015.

12 Gandhi R, Perruccio AV, Mahomed NN.

Surgical management of hip osteoarthritis. CMAJ. 2014 Mar 18;186(5):347-55.

13 Sankar W, Horn D, Wells L, Dormans J.

The Hip. In: Kliegman R, Behrman RE, Nelson WE, editors. Nelson textbook of

pediatrics. Edition 20 ed. Phialdelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016. p. 3274-83.

14 Schmitz M, Rush J, Milbrandt T.

Pediatric Orthopaedics. Miller's review

of orthopaedics. Seventh edition. ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016. p.

264-334.

15

Chalmers CR, Smith CP. MRCS A essential revision notes. Knutsford: PasTest;

2012.